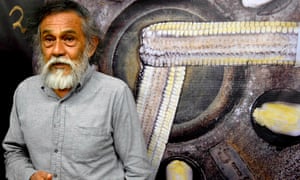

| Francisco Toledo, activist and artist known as 'El Maestro' in his native Mexico – obituary

Though Toledo would travel widely during his career, studying in Paris and working in New York City during the 1980s, it was to Oaxaca that he would ...

|

Francisco Toledo obituary

Mexican artist whose work paid homage to the myths he imbibed growing up in an indigenous Zapotec family

The Mexican artist and activist Francisco Toledo, who has died aged 79, was best known for paintings, prints and ceramics that paid homage to the myths and stories he imbibed growing up in an indigenous Zapotec family, depicting a vast menagerie of real and fantastical animals, often on unconventional yet traditional grounds such as ostrich eggs and tree bark.

Playful depictions of monkeys were plentiful, but there was a darker side to his work, such as the red-stained ceramics he made in response to Mexico’s drug wars, Duelo (Mourning, 2015), and the overtly sexual, phallus-centered self-portraits he returned to throughout his career.

“Toledo’s is the art of shamanism,” wrote Christopher Goodwin in the Guardian in 2000, on the opening of a major exhibition of his work at the Whitechapel Gallery, London. While much of his subject matter came from pre-hispanic art, there was also, according to Toledo himself, who lived in Paris for several years in the 1960s, “the influence of Picasso, Miró, Dubuffet, and all the art that does something with primitivism”.

“Toledo is no whimsical folklorist,” wrote Laura Cumming in a review of the Whitechapel show, “but a draughtsman in the grand tradition. His etchings have been compared with Goya and Ensor and his watercolours elaborate a whole series of invented hieroglyphs and signs as delicate and toylike as anything by Klee.”

Toledo was one of the seven children of Florencia Toledo Nolasco and Francisco López Orozco. He often said he was from Juchitán, a city with a rebellious reputation on the pacific coast of Oaxaca where his family had deep roots, but he was born in Mexico City and spent his early childhood in Minatitlán, on the Gulf side of the state of Veracruz, where his father, a former leather worker, had a successful small business selling sugar.

Francisco grew up surrounded by many of the animals that would later inhabit his art, from the birds in the forests to the turtles in the marshes, and the tapirs, rabbits and iguanas that wandered around his home before they ended up in the pot. There were also a lot of insects, not least swarms of wasps attracted by the sugar at the family home that meant its members had to swipe their way out of the building with wooden rackets. “I doubt anybody has ever evoked the delirious hum of insects better,” Cumming later wrote in her review, “five pencils, tied together and zig-zagged in a skittering dance across a scrap of paper.”

He always loved drawing, but Toledo’s future career was triggered by his father’s decision to send him to secondary school in the city of Oaxaca, in the hope that he would become a lawyer. Instead, he started art classes and discovered a library where he marvelled at reproductions of the likes of Goya and William Blake.

By the time Toledo was 17 he was in Mexico City studying lithography. Soon he was being mentored by an influential gallery owner, Antonio Souza, who in 1959 put on his first exhibition, which travelled to the Fort Worth Art Center in Texas. The money made from the sales enabled Toledo to travel to Paris, where he was taken under the wing of Rufino Tamayo – another Zapotec artist who had already found success – and the writer Octavio Paz. He was 24 when he had his first exhibition in the French capital, at Galerie Karl Flinker, putting him firmly on the road to international recognition.

Rather than embrace this meteoric rise, Toledo decided in 1965 to return to Mexico and immerse himself in his cultural heritage. To begin with this meant a period in Juchitán, and in later years it meant a wandering life in which he would produce art wherever he happened to be – Mexico City, Paris, New York – though he slowly but surely became ever more intertwined with Oaxaca, where he eventually settled in the 80s.

Toledo used the considerable income from his art to set up several cultural institutions in his home city, supporting new artists and broadening access to the arts, including the Graphic Arts Institute of Oaxaca, the Oaxacan Museum of Contemporary Art, the Jorge Luis Borges library for the blind, and a botanical garden.

He also became a social activist, spearheading campaigns such as one that successfully halted the opening of a McDonald’s restaurant in Oaxaca’s central plaza in 2002 (with the slogan, “Tamales Yes, Hamburgers No”). In 2014 he printed kites with the faces of 43 missing student teachers who had been “disappeared”, and flew them through the city centre.

He continued to show internationally, and was included in the Venice Biennale in 1997. The following year he received the Mexican national prize for arts and sciences (Premio Nacional de Ciencias y Artes).

Two marriages ended in divorce. Toledo is survived by his third wife, Trine Ellitsgaard, a Danish weaver whom he married in the mid-80s, and their children, Sara and Benjamín; by two children, Laureana and Jerónimo, from his second marriage, to Elisa Ramírez Castañeda, a poet; and by a daughter, Natalia, from his first marriage, to Olga de Paz Vicente.

• Francisco Benjamín López Toledo, artist and activist, born 17 July 1940; died 5 September 2019

Since you’re here...

... we have a small favour to ask. More people are reading and supporting The Guardian’s independent, investigative journalism than ever before. And unlike many new organisations, we have chosen an approach that allows us to keep our journalism accessible to all, regardless of where they live or what they can afford. But we need your ongoing support to keep working as we do.

The Guardian will engage with the most critical issues of our time – from the escalating climate catastrophe to widespread inequality to the influence of big tech on our lives. At a time when factual information is a necessity, we believe that each of us, around the world, deserves access to accurate reporting with integrity at its heart.

Our editorial independence means we set our own agenda and voice our own opinions. Guardian journalism is free from commercial and political bias and not influenced by billionaire owners or shareholders. This means we can give a voice to those less heard, explore where others turn away, and rigorously challenge those in power.

We need your support to keep delivering quality journalism, to maintain our openness and to protect our precious independence. Every reader contribution, big or small, is so valuable.