David Byrne played Mexico City on Tuesday, April 4. It’s still early in

the tour and he’ll head back to the U.S. after a few more dates in Mexico. Trust me, go see David Byrne, even if you only have a vague appreciation for Talking Heads. I don’t review every concert I attend, not even all the great ones. But this was more than a concert, it was a

show.

The stage was totally empty—no amps, cables, or drums kits. It was bordered by hanging strings of light that looked like sparkling curtains, which the players passed through as they exited and reentered the stage.

The 12 musicians and singers—I call them “players” because they were more than musicians and singers, but cogs in a cohesive musical machine—were in constant motion, carrying their instruments as they walked, ran, and danced around the stage. They had bare feet and wore matching suits, though at times the lights made the suits change color, from a silvery grey to a light brown.

A full half were drummers, so it didn’t matter that their feet were unavailable for the music, since all the drums you’d find on a typical drum kit were divided among the six of them. Between songs they disappeared behind the curtain of glowing strings and reemerged with different drums, usually the ones you’d see in the drumline of a marching band. They carried big bass drums, single snares, bongos, shakers, talking drums, smaller hand drums like djembes, thin sideways drums that looked like the Irish bodhrán, and the array of toms used by marching bands.

With so many drummers, every song was a masterclass in rhythm. As they moved around the stage, usually in formation, you could watch specific drummers and hear exactly what they were playing and how it fit into the larger sound, even if it were something as simple as a shaker.

Three of the remaining six were singers, Byrne and two more, one male and the other female. At times they played a small drum or shaker, but were mostly free to dance. Byrne played guitar a few times but spent most of the show without an instrument. When he did play guitar, it was usually for a solo. For instance, I learned that the weird sound after the chorus in “Blind” is actually Byrne doing a high bend on the guitar.

The other three players were a guitarist, bassist, and keyboardist with the keyboard hung from his neck. With these three taking care of everything besides percussion, the music had an almost stripped-down feel, despite all the drums. Most Talking Heads songs were from their big-band funk era, with three each from Remain in Light and Speaking in Tongues. Therefore these three musicians handled parts originally played by up to six people: two keyboardists, sometimes two bassists, and two or three guitarists.

The musicians were at once virtuosic and tasteful. Elements of Talking Heads songs were sometimes faithfully rendered, like the unmistakable keyboard solo in “Naive Melody (This Must Be the Place),” and sometimes given a fresh interpretation, like the incredible guitar solo during “The Great Curve,” which as the last song of the first encore seemed the climax of the show. But even though the guitarist was obviously exceptional, she usually only played sparse rhythm parts, saving the big solos for certain moments.

Byrne introduced the bassist as Bobby Wooten—is he a member of the Wooten clan that includes Flecktones Victor Wooten and Future Man? He was the rock, the glue, the solid connection between the two melody instruments and the frantic polyrhythmic chorus of drums.

About half of the show were Talking Heads songs, and the other half were a mix of songs from Byrne’s new album American Utopia and a few outliers from his solo career. The Heads songs included big hits, of course, but also many songs the casual radio listener might not know, like “I Zimbra” and “Born Under Punches (The Heat Goes On),” both well-suited to the peculiarities of this band.

Perhaps the catchiest song from American Utopia is “Every Day is a Miracle.” With its bright and expansive chorus, it could have appeared on a later Talking Heads album like True Stories, although its dissimilar music clearly represents a different age and attitude. It got the crowd swaying as much as any of the old classics.

Other American Utopia songs have a more divergent style, such as the grinding electro chorus in “We Dance Like This.” But the lyrics are pure Byrne, with topics ranging from declarations of uninhibited weirdness to abstract social commentary.

I have a much better appreciation for these American Utopia songs after having seen them performed live. Each seemed to tell a story, both lyrically and through the choreography, similar to how the motions of ballet dancers tell wordless stories on the stage.

This was also true for his other solo material. In “I Should Watch TV,” Byrne sang to himself in front of a mirror. In “Dancing Together,” one bongo-playing drummer ran loose in front of the rest of group, who followed at a distance, seeming to chase and chastise him.

Besides these more thematic motions, the choreography was a mostly a mix of marching band, flat-footed ballet, and organized chaos. The arrangement of the players sometimes recalled Talking Heads essentials like the concert film Stop Making Sense or Byrne’s spastic dancing in the music video for “Once in a Lifetime.”

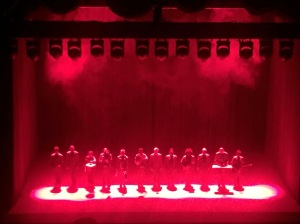

During “

Everybody’s Coming to My House,” they began in two lines that alternately advanced and retreated, all while drenched in red lights. During “Burning Down the House,” they formed a large + that spun around the stage, to later break into other formations. And in most songs, the two singers danced around each other in an exaggerated tango.

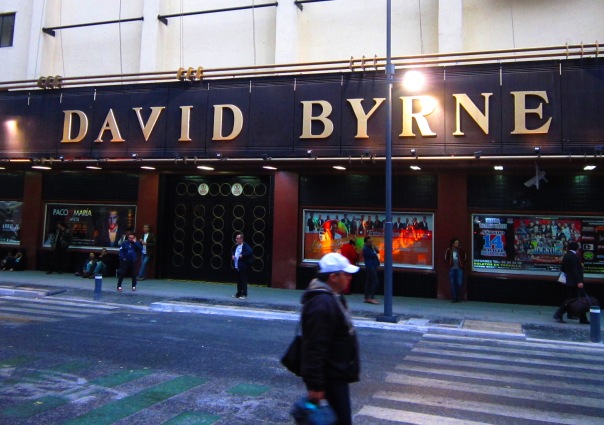

The venue was perfect—the large and ornate Teatro Metropolitán, a classic theatre in the heart of downtown Mexico City, one block away from the central Alameda park. The street outside was lined with vendors selling bootleg t-shirts, posters, and coffee mugs, a contrast to the tall columns, gold trim, and plush carpets of the interior.

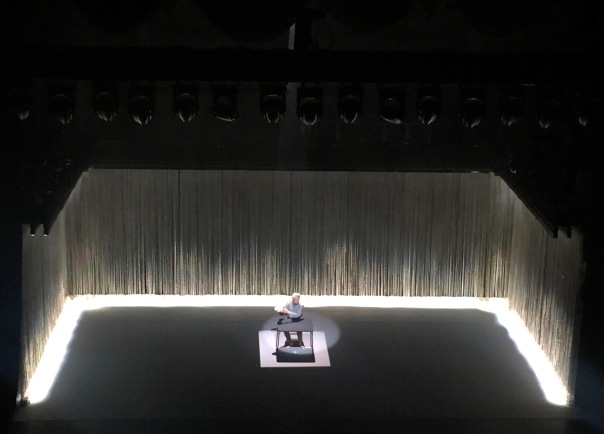

Immediately after openers Mexican Institute of Sound left the stage, the crew rushed out and took away their gear, leaving the stage bare. Four workers with long dust mops came out and swept the floor clean. Then they brought out a square table and placed it in the exact center of the stage.

A three-sided rack of what looked like a lighting rig was lowered down to just above the stage, hanging at its far edges in a kind of open square. It was about now that I noticed there was no house music. Strange to have silence between bands—but it wasn’t silent, of course, with people all around talking, looking for their seats, and buying snacks and milkshakes from suit-wearing girls squeezing through the crowded aisles. No beer, though—for that you had to go downstairs to the bar and get in line.

But wait—it wasn’t actually silent underneath all the voices and shuffling feet. Some sound was coming out of the speakers, a kind of soft white noise, a faint electronic humming just faint enough to be nonchalant and nearly unnoticeable. But as the minutes passed, it soon changed from a steady hum to almost like crickets. There was no ignoring it now.

The crowd kept talking while the sound grew louder. A crew member brought out a chair and put it behind the table. The stage went dark and a spotlight shone on the table and chair. The house lights stayed on, however, so no one seemed to notice. But they must have noticed the sound, which continued to evolve, first into another constant white noise, then to something like rain. But not real rain—like the crickets it had an electronic, created quality. Eventually it became chirping birds, loud and insistent, but intriguing like the rest. Suddenly the house lights went out. The show had begun.

The rack of hanging strings of light quickly rose above the stage. David Byrne walked alone though the brilliant cords and sat at the table. He picked up a big white object—a human brain, which he alternately cradled and swung about, pondering it and singing to it during “Here,” the atmospheric first song with lyrics about neurons, aliens, and hallucinations.

The musicians emerged for the second song, got into formation, and the show went on, a spectacle of sound and rhythm, drums and voices, synchronized motions and warm lights.

The show had two encores, both noteworthy. The first began with a song called “Dancing Together,” which Byrne introduced by saying he wrote it for Imelda Marcos, calling her something like a “high society lady.” This was followed by the rapid groove of “The Great Curve,” probably the musical highlight of the night. After this, the players didn’t only bow to the applauding crowd, but also to each other.

The band left the darkened stage and returned shortly for a second encore. They carried no other instruments besides drums. Byrne spoke again, saying that they’d play a song written by a friend with lyrics adapted to Mexico. (

Setlist.com tells me it was “Hell You Talmbout” by Janelle Monáe.)

The chant-like song was in Spanish, beginning with repetitions of “Cuarenta y tres” (43), referring to the 43 students who disappeared from the small town Ayotzinapa in 2014, a still-unresolved crime widely believed in Mexico to have been committed or at least approved by the government.

The chant then became “Diga su nombre, diga su nombre!” (Say his name, say his name!), and individual singers responded by calling out names, obviously those of the missing 43 students.

This was the only overtly political message of the night. In the context of his American Utopia, he reminded the crowd of their very real Mexican dystopia.

In the same way that this show was more than a concert, David Byrne is more than a musician, but an activist, writer, and interesting character in many respects. As a lifelong cyclist, I greatly appreciate his promotion of urban cycling all around the world. Anyone interested in music would love his book

How Music Works. And, of course, Talking Heads are legendary, one of my god bands—if you aren’t familiar with their music, get on YouTube and watch

Stop Making Sense right now. Fanatic Heads worshipers like me are bound to enjoy

American Utopia,a worthy addition to his legacy, especially if you can catch it live.

Thanks Mr. Byrne, and come back to Mexico soon!

Consultados al respecto, algunos habitantes mostraron su inquietud por el ocultamiento de información de parte de la agencia e integrantes del cabildo municipal, pues aseguraron que hace unos días se realizó una reunión casi a escondidas con algunos ciudadanos afines a la representante interna, y se prevé que el domingo próximo haya un nuevo encuentro con el mismo recelo.

Consultados al respecto, algunos habitantes mostraron su inquietud por el ocultamiento de información de parte de la agencia e integrantes del cabildo municipal, pues aseguraron que hace unos días se realizó una reunión casi a escondidas con algunos ciudadanos afines a la representante interna, y se prevé que el domingo próximo haya un nuevo encuentro con el mismo recelo.