Back to On the Road with John Tarleton

A Wave of Change Inundates Zipolite

by John Tarleton

January 1997

Table of Contents

I. Arrival

II. Adelina and Pedro's Store

III. Sidewards Glances

IV. Cops, Nudity and a New Church

V. Close Calls

VI. The Long Shadow

VII. Return

Part I: Arrival

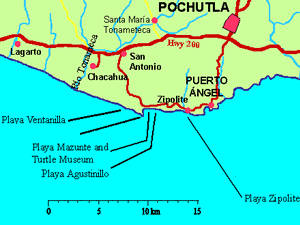

ZIPOLITE, Mexico — The first time I came to Zipolite the paved road (and the bus) stopped at the sleepy fishing town of Puerto Angel. Sun-worshiping backpackers had to disembark by the concrete fishing pier and walk the final five kilometers to Paradise.

Only a few bold (or desperate) taxi drivers braved the trek, weaving cautiously around gaping potholes in the steep, winding, bumpy dirt road. Most travelers endured the baking heat and lugged their own stuff up over the hills to Mexico¹s only nudist beach.

"In '89, '90 and '91, this place was still virgin territory," Pedro Guerrero would say, looking back a few years later. "There was no highway and there were no police.....There were turtles. There was total nudism on the beach and the best-looking foreign women. Pot was everywhere. And it was the best, the very best."

Centuries before hippies discovered the arcing, mile-long white sand beach in the early '70s, the Zapotec Indians were drawn to its shores by the giant sea turtles that periodically crawled out of the sea on the full moon to lay their eggs in the sand. Observing the large, powerful waves and the tricky currents, the Zapotecs gave the beach its name of Zipolite, which translates in English to "Beach of the Dead".

Part II: Adelina and Pedro's Store

The second time I came to Zipolite the paved road had been extended through the end of town. In front of Adelina and Pedro Guerrero's house, sleepy dogs and small children had to jump out of the way to avoid being hit by speeding taxis.

I had first found Adelina the year before sluggishly swatting away the swarms of flies that hovered over bunches of shriveled black bananas. She was sitting on a stool in the shade in the storefront of her family's unfinished, one-story concrete house. She already had four children and was seven months pregnant with her fifth child.

Adelina laughed a lot and her short, moppish black hair bounced over her forehead when she moved. When I would walk in barefoot through the open doorway, her eyes would brighten and she would call out: "pasale, pasale" ("come in, come in"). Besides the bananas, there were a few green oranges, an occasional pineapple and packaged cookies. It was the off-season and business was light. Every peso was important for Adelina and her family.

Now back for a second time, I found Adelina and her husband Pedro and their children hard at work each morning operating a tortilla-making machine that they had somehow skimped together the money to buy. The machine could produce 400 pounds of tortillas per hour or 4,000 pounds in a busy, ten-hour day.

Neighbors crowded around the storefront window early in the morning to buy tortillas for 800 pesos per kilo (1 kilo=2.2 lbs.). Large diesel busses chugged by Adelina¹s house full of young tourists and their backpacks. The world was now discovering Zipolite.

Part III: Sidewards Glances

Concrete was coming into vogue the third time I visited Zipolite. The open-aired, thatched-roof palapas where one could sling up a hammock for a couple dollars per night were giving way to sturdier, more expensive two-story cabañas.

The Playa del Amor had been overrun. A restaurant and a fancy palapa had been built atop the bluff overlooking the tiny, isolated cove that is adjacent to the far end of the beach. The pale moonlight would have to guide lovers to other, more distant coves.

Soldiers were now patrolling the beach during the day. A detachment of four, fully- armed marines rode over each afternoon from the naval base in Puerto Angel, and, trudged through the soft white sand in their black combat boots and their dark blue uniforms.

They ostensibly were searching for drugs, especially any signs of the ubiquitous marijuana plant. Their sidewards glances indicated, however, that they were more interested in the sunbronzed gringas who lay naked in the sun. Great were the torments, no doubt, that these teen-age conscripts suffered when they tried to go to sleep at night back at the barracks.

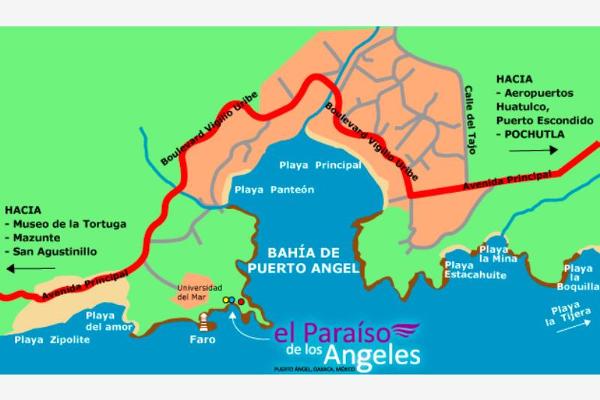

The government had extended the paved road another twelve kilometers to the quiet, obscure fishing village of El Mazunte and then beyond. Also, the government had rapidly erected Universidad del Mar (UMAR), a new university dedicated to oceanographic studies that was located on the coastline between Zipolite and Puerto Angel. Zipolite¹s tranquil, undimmed night sky was now rudely lit each night by the white artificial lights that glowed from nearby hilltops.

Tortillas were now selling at 1,100 pesos per kilo at Adelina and Pedro¹s store, and business was booming. Adelina, however, was tense and hurried; snapping at people who weren't sure how many tortillas they wanted or who didn't have their money ready when she placed their stack of hot, steaming tortillas down on the counter. She wasn't smiling and laughing as much as she used to.

Part IV: Cops, Nudity and a New Church

The fourth time I went to Zipolite the marines had finished building a small, military barracks on the eastward end of the beach. They could now police this notorious but harmless hippie haven 24 hours a day.

Nudity appeared to be tapering off as more tourists arrived. As for the sun, it had become more fierce in just a few years. I now wore a floppy hat and a t-shirt in the mid-day sun lest it sizzle my tan, brown skin.

Nudists could mostly be found reclining on or around the rocks on the far west end of the beach. After coming to Zipolite several times, it seemed more strange and burdensome to go into the water with a bathing suit on.

Still, I would often get the raised-eyebrow look from people when I told them about Zipolite; as if people who swim in the ocean or tan themselves without a bathing suit are somehow more lurid and depraved than those who do. We all put our bathing suits on and take them off. Some just do so more frequently than others.

Like many others, I was self-conscious the first time I took off my bathing suit before running out to dive headfirst into the waves.

I went down near the shore and looked both ways, as if judging whether or not to cross a busy intersection. I was certain everybody was looking at me. But when I strode out of the foam a few minutes later, I realized that I had been silly. Nobody gave a damn whether my dangle was blowing in the breeze or not.

Besides the military barracks, construction was now also underway on Zipolite's first-ever church. It was located in the center of town, behind the taxi stand and off to the side of Fernando Arellanes's grocery store.

Fernando was a congenial, energetic, 40-year-old business man whose fruit and vegetable stand had grown into a small grocery store since my first visit to Zipolite.

Before coming to Zipolite in 1990, Fernando had been a coffee grower in the mountains of Oaxaca. His business had gone bust in the late '80s when world coffee prices collapsed. Since then, his fortunes had turned for the better once again.

One morning Fernando was sitting on a stone wall outside his store, bouncing a baby on his knee. It was his fifth child but his first son.

"Little Fernando here is going to be the last one," he said. "I am a fortunate man to finally have a son."

Fernando walked around in dusty trousers and flip-flops. He was always in a good-natured mood, bantering in Spanish or broken English with the long-haired travelers who milled about in his low-slung store. He kept up with current events. And when business slowed, he would ask customers their impressions of how things were going in their native countries. He was sincerely interested in the lives of the people who were making him a prosperous man.

Part V: Close Calls

The fifth time I went to Zipolite five people nearly drowned during my first week back.

The church had been completed. A crucifix and a framed picture of The Virgin of Guadalupe hung from an otherwise bare, freshly whitewashed wall.

Adelina and Pedro were still working hard. I caught a glimmer of a smile on her face one morning as she sold tortillas in the storefront window while I rode by in a colectivo. Tortillas were now selling for 1,600 pesos per kilo. And, they were adding a second story to their house.

The soldiers also kept busy. They patrolled during the day and sometimes by night, hoping to sneak up on a campfire of pot-smoking hippies before they could hide their stash.

Sergio¹s Story

When I first arrived back in Zipolite, I spent an evening talking with Sergio. He was a young Mexican who managed a coffee house that was an adjunct to one of Zipolite¹s most popular hippie lodgings. Before, he had been a marine biology major down the road at UMAR. Then, Mexico¹s outgoing president and foreign currency speculators had sucked billions of dollars out of the treasury and thrown Mexico into its worst economic crisis in 65 years.

Sergio stood on the coffee house¹s balcony after work and looked wistfully out at the moonlit water. Bongo drums echoed in the night from the bonfires that flickered on the beach below.

"I loved my studies and I made good grades," he said. "But, my father¹s business collapsed when The Crisis hit. And my family couldn't afford to send me to school any longer."

Sergio¹s wage was a pittance and the tip jar on the counter had been near-empty. Still, he desperately hoped to save up enough money to re-enroll at UMAR. If he could, he would finish his undergraduate studies and begin his life's work: dolphin research.

Sergio's heart opened like a vulnerable flower as he spoke of his beloved dolphins. He pointed to the bay below and described how he would come up to the balcony at dawn to watch schools of dolphins swimming across the open waters.

He thought dolphins to be kinder and more sociable than humans and at least as intelligent. And he believed that we all had much to gain from further research into these mysterious marine mammals who gave up on terrestrial life 50 million years ago to return to the ocean.

I asked Sergio why he didn't keep ongoing to school part-time while he worked. That wasn't possible, he explained. UMAR only permitted full-time students. A student had to be on campus from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. This university wasn't for the kind of students who had to work their way through school.

Rescue

It was January, the peak of tourist season. And the full moon was approaching, which meant trouble.

One moment everything was fine - young, beautiful people from all over the world were basking in the sun. And then, all the beauty and horror of Zipolite would collapse into a single, terrifying moment as people would start running down the beach en masse, shouting at each other: "Someone's drowning!" "Someone's drowning!".

The first time it was a swarthy European man trapped about 100 yards out in the swirling current. His round head bobbed above the choppy waters. The soldiers were nowhere to be seen. The lifeguard was any good swimmer who came along with a surfboard, rope and life preserver.

"Hurry up! Hurry up!" someone shouted. "He's been out there a longtime."

A young Mexican man arrived at that moment with his surfboard. He calmly entered the water and began paddling out to the drowning man.

Just then, a blond-haired American man came running full speed from the far end of the beach and plunged into the water. Though exhausted, he started swimming out toward the drowning man.

Ducking beneath the waves, the young Mexican soon reached the drowning man. He tossed him a life preserver and started towing him to shore. When the man who nearly drowned reached shallow, knee-deep water, two other men came out to help him to shore.

The man wore a fluorescent green, string bikini. He moved shakily as he staggered ashore. When he reached firm, dry land, he fell to the hot sand. And his whole body quivered with terror and joy. Suddenly aware of the crowd that had pushed in near him, the man rolled over on his belly and pressed his face down and then resumed sobbing; his warm, salty tears moistening the sand.

Bitter Memories

I watched this spectacle with a sinking feeling in my stomach, with memories of how I had once crawled ashore like this during my first visit to Zipolite.....

.....of how I had wandered out into the waves in a dazed, early-morning reverie following the previous night's rendezvous at the Playa del Amor, of suddenly being swept off my feet in seven-foot deep water and feeling a powerful current propelling me southwestward out to sea.....

......of slowly fighting my way back against the ocean (never thinking to swim laterally out of the current), of reaching four-foot deep water and being able to touch bottom but not hold my position, of waving and calling out to a near-empty beach where only an absent-minded, old man walked alone at dawn.....

.....of a burning anger rising up in me and then fighting my way forward again with one last furious burst of energy, of reaching the shallow intertidal zone and crawling to shore where sand crabs skittered in and out of holes they had dug in the wet sand.....

.....of my muscles burning from the exertion and wishing at that moment that I had a woman beneath me to embrace as I fell to the ground and instead gratefully embraced the firm, unmoving sand.....

Another Rescue

"Someone else is drowning!" "Someone else is drowning!"

I looked up as the crowd quickly moved away from the rescued man in the green string bikini who was now left alone in the sand. A couple of surfers were already in the water with their boards. Too tired to make it back to shore, the blond, American man was floundering in the waves.

Soon they had him on shore. I recognized him from a couple of years before and went over to talk to him. He nodded incoherently when I said hello.

He then got up and staggered toward the water. Two people had to restrain and lead him back to the sand. The blazing sun and the tempestuous sea were breeding a strange madness in those who had come to The Beach of the Dead.

Part VI: The Long Shadow

By the sixth time I came to Zipolite it had 65 palapas/restaurants, 15 storefronts, a couple of discotheques, a trailer park, a jail, a rural health clinic, a laundromat and an exchange house. The exchange house ("Casa de Cambio") dealt in ten currencies and was open seven days a week.

Across the way from the laundromat, idle taxi drivers milled around in the dust next to the empty church waiting for rides. Windblown trash was pinned against telephone poles along the side of the road. Nearby, Fernando was in a cheerful mood.

"How are you my friend!" He called out, instantly recognizing me when I ducked through the doorway to his store.

Adelina and Pedro were still working on the second story of their house. A kilo of tortillas now sold for 3,000 pesos.

Tour busses chugged through town closely followed by VW vans packed with Mexican families. Christmas was near and hordes of "chilangos" from Mexico City poured into the area. Quickly bored with Coney Island-style atmosphere, I drifted a few kilometers up the coast. Zipolite was no longer an isolated, counter-cultural haven, but, a full-fledged tourist town--as it had been for several years.

Footprints in the Sand

I found a family of Mexican hammock-makers that let me camp on their land overlooking the ocean. Sleeping in the open air beneath a thatched roof, I awoke to the first reddish-gray streaks of dawn. I jogged and practiced yoga early in the morning, and I sat and wrote at a homemade wooden desk during the day.

Looking out from where I wrote, I could see footprints crisscrossing in the sand below, pelicans plunging into the foamy white waves that were crashing and receding along the shoreline and then the deep blue of the ocean that stretched to the distant horizon and onto the other side of the world.

There was a steady trickle of travelers coming up the coast from Zipolite. The tide would only grow stronger. The process was repeating itself all over again. Civilization is our late-afternoon shadow. Wherever we run, it follows along with us.

Part VII: Return

I hiked back down the coast to Zipolite one day and talked with two familiar acquaintances, Pedro Guerrero and Fernando Arellanes.

Pedro was gloomy about Zipolite¹s future. He was ready to move his wife, his five kids and his tortilla-making machine back to his hometown in the Central Valley of Oaxaca and rent out the house that he and his family had so tediously constructed.

"Zipolite has been going downhill since 1992, when the highway arrived," Pedro said.

"It used to be here," Pedro continued, his hand at his chin. Pedro¹s hand then fell a little each time he mentioned another year. By the time he arrived at 1996, his hand was at his knees.

"The cars run around really fast on the road. And now the tourists want hotel rooms with fans. They want to be able to live like a king."

Different Concerns

Fernando was also concerned about Zipolite's rapid transformation. But as usual, he remained optimistic. And his concerns were more those of a man who is determined to stay where he is.

"This is a town of people from other places," he said. "There are people from other parts of Oaxaca, other parts of Mexico and from abroad. It's disorganized. People don't know each other.

"There's a lot of theft here. You always have to keep your eyes open. If you look the other way for one moment, someone will grab your things. And the police are never there when they rob you.

"This was a pretty place. But, we have to accept the change. Man has the capacity to evolve himself. We can't remain behind. We have to evolve and go with the change."